Self-Help Buddhism

The Death of Western Buddhism: Part 6

Imagine a sleek office conference room at dawn. The lights are dimmed, the PowerPoint is cued, and twenty white-collar warriors clutch their yoga mats like battle shields. They’ve come to fight stress with ten minutes of seated breathing. Each and every mindful minute is tracked on the corporate wellness app, each breath a data point in their personal performance review. A bell chimes. They inhale. They exhale. Then they fill their coffee mugs, ready for another day of strategic alignment and KPI warfare.

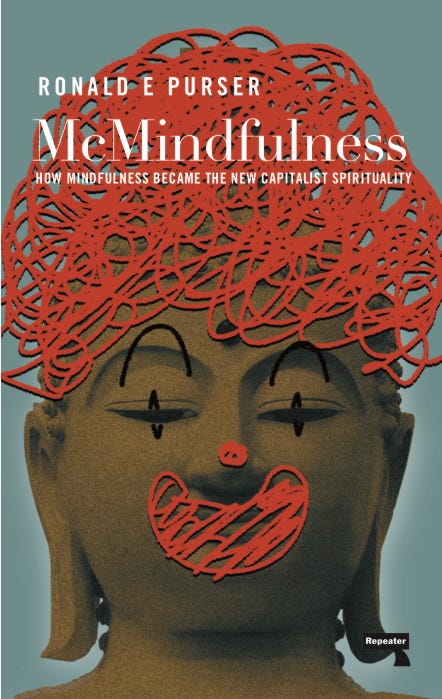

This is McMindfulness in a nutshell: an industrious, privatized spirituality that offers immediate relief—like a sugar-rush meditation gumdrop—but one that quickly dissolves, leaving the same craving mind intact. In this therapeutic consumerist paradigm, the individual is both client and product, endlessly optimizing the self for peak productivity. It may flatten anxiety curves, but it deepens a more insidious wound: the wound of alienation.

The Genealogy of “Spiritual DIY”

Long before Fitbit Zen and mindfulness apps, the Western privatization of spirituality emerged through a series of ideological shifts that recast communal religious practice as a solitary project of self-improvement.

In the early 19th century, Transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau championed the primacy of individual intuition over external authority, laying philosophical groundwork for spiritual self-reliance. By mid-century, pioneers of New Thought like Phineas Quimby and Mary Baker Eddy taught that one could will riches and health into existence by sheer mental force. Penny pamphlets offered step-by-step guides to manifest the self and achieve the American Dream.

Then, in the early twentieth century, pragmatist psychology and self-help salesmanship fused: William James recoded religion as workable experience, while Dale Carnegie’s bestsellers reframed moral discipline as a technique for social lubrication and professional success—spiritual practice became a skills toolkit for personal achievement rather than a path enhancing community cohesion.

Fast forward to the 1960s counter-culture: we find the mushrooming of Maslow inspired human-potential workshops and psychedelic-fueled retreats that fused Eastern meditation with Western psychobabble. In 1979 Jon Kabat-Zinn’s MBSR arrived as the clinical heir to that movement when he repackaged Buddhist mindfulness as evidence-based stress relief. The robes were gone, the Sangha was gone, and in its place stood a row of therapy chairs and a research lab.

Into the 1990s and 2000s, neuroplasticity research and bestselling pop-science made meditation a matter of brain rewiring, a reframing that nurtured the rise of secular retreats, corporate wellness courses, and the explosion of the now ubiquitous “mindfulness” training that popped up everywhere—in schools, corporations, hospitals, prisons, and even in government agencies including the U.S. military. Buddhist Practice was ingested and transformed into a productivity hack validated by fMRI scans.

In the 2010s, digital wellness pioneers like Headspace and Calm turned meditation into a subscription-based service, gamifying calm through streaks, badges, and push-notification reminders. By the 2020s, wearables and AI-curated meditation playlists have personalized every breath, cementing an ethos of spiritual DIY in which inner peace is just a download away—no teacher, lineage, or community required.

Through each phase, the social, ethical, and communal dimensions of practice have been peeled away in favor of techniques marketed for individual optimization. The result is an ecosystem where spirituality is consumed like any other personal enhancement product—and where vital community support—the Sangha—is all but forgotten.

The Paradox of Private Peace

Here’s the cruel joke: McMindfulness does exactly what it promises. It lowers blood pressure. It tames the chattering mind. But—like a soft balm applied to a gaping wound—it never addresses why the wound exists. It soothes the symptom without treating the disease.

McMindfulness reframes anxiety as a private malfunction to be remedied by solo practice, obscuring its systemic roots in economic precarity and social isolation. Programs like MBSR tout neurobiological benefits —reduced amygdala activation and increased prefrontal cortical thickness—but these individual gains occur in isolation, without addressing structural causes such as workplace exploitation or community breakdown.

Underneath the surface calm, social alienation simmers. When anxiety is redefined as a private malfunction, its structural roots—economic precarity, social fragmentation, digital burnout—remain untouched. We become calm cogs in the wheel of production rather than awakened catalysts for change. Efficiency replaces awakening. Resilience becomes compliance. Mindfulness morphs into an entrepreneurial hack, a productivity enhancer sold back to the worker.

By treating mindfulness as a personal performance metric, corporate wellness initiatives transform practitioners into data points on productivity dashboards. Employees log “mindful minutes” on wearables, boosting focus and resilience—but also reinforcing the notion that the solution to burnout lies in better self-management rather than improved labor conditions. As Ron Purser and David Loy observe, this is “capitalist spirituality” that co-opts mindfulness to sustain unjust systems rather than challenge them.

Moreover, McMindfulness dissolves communal bonds that historically anchored Buddhist practice. Without Sangha, practitioners lose ethical accountability: there is no collective witness to check self-deception or shadow behaviors. Bhikkhu Bodhi warned that divorcing mindfulness from the Noble Eightfold Path and community ethics reduces practice to “bare attention” devoid of moral framework, allowing spiritual techniques to serve self-interest rather than liberation, turning the Buddha’s teaching into a ‘mere adornment’ for a comfortable life.

Critics like David Loy highlight how privatized meditation functions as a palliative, soothing distress without altering the conditions that generate suffering. He argues that focusing inward leaves practitioners “adapted to systemic injustice” rather than empowered to address poverty, racism, and environmental destruction. Engaged Buddhists like Thich Nhat Hanh emphasized that individual calm is incomplete without collective action to transform social roots of suffering. The more skillful we become at “bare attention,” the more we reinforce the very attachments Buddhism cautions against: attachment to self, to control, and to achievement. We tidy our inner storefront while the neighborhood crumbles.

Finally, empirical research links loneliness—a hallmark of privatized culture—to increased anxiety, depression, and even mortality. One large-scale survey found that people relying solely on apps and solitary practice report lower social connectivity and greater existential distress over time. In contrast, Sangha participation correlates with higher well-being and sustained practice commitment.

Thus, the very methods that McMindfulness uses to reduce anxiety simultaneously deepen alienation, reproducing a model of the self as a self-contained project under market logic. True Buddhist liberation, by contrast, demands healing not only of personal distress but of our interdependent relationships and the structural conditions that give rise to suffering.

Buddhism’s Radical Call to Commune

You see, true Buddhist practice never was a solo act. The Buddha’s first community—the Sangha—was a radical experiment in interdependence. Monastics and laypeople lived, practiced, and cared for one another in a collective pursuit of liberation. Ethical conduct was not optional; it was the bloodstream of the practice. Together, practitioners bore witness, corrected one another’s blind spots, and supported one another through life’s storms.

This dynamic is not some quaint ritual relic. It remains essential to dismantling the narcissistic enclosure of privatized spirituality. In Sangha, the self dissolves into a shared field of practice. One person’s insight becomes nourishment for all; one person’s struggle becomes a call to collective compassion.

From Me to We: A Call to Rebuild

If McMindfulness is the symptom of a culture enthralled by its own reflection, then Sangha is the remedy that points us beyond the mirror. The future of Buddhism in Western shores depends not on perfect technique, but on collective transformation.

Lean into community. Bring your anxiety before a circle of fellow travelers rather than a dashboard. Let your practice be held by others, and hold others in turn. Because liberation is not a private metric to be scored and optimized—it is a radical, shared unfolding, a storm of blossoms raining down when the silence of communal presence truly lands.

It’s time to move beyond the narcissism of self-help and rediscover that Buddhism was never meant to be a solo project. As artist David Choe suggests, we can either “die slow alone or heal fast together”. The path home leads through one another.

The image of white collar warriors clutching yoga mats like battle shields is absolutley perfect and kinda haunting. Youve really nailed how mindfulness got flattened into another productivity hack instead of something transformative. I've been in those corporate wellness sessions and the vibe is always weirdly performative, like everyone's just ticking a box. This whole series has been a fascinating read.